#Tags:

GreeceΑλέξης ΤσίπραςTsipras 2.0: Déjà Vu All Over Again?

BY KONSTANTINOS KANELLOPOULOS

On Oct. 22, the French President Francois Hollande, who pro-claimed himself as “Greece’s number one supporter,” exhibited his solidarity and support to Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras during a two-day visit to Athens. Accompanied by various representatives of French companies and key members of his cabinet, the French President praised the Greek leader’s “courage” in accepting the harsh bailout terms and expressed his determination to support Tsipras’s reform drive, despite the controversial anti-austerity pledges he once made.

While Hollande’s visit to the Greek capital comes at a crucial moment, and it exemplifies the resuscitation of France in European affairs, more importantly, it is also a first step on the part of Tsipras’s necessary transformation from a populist demagogue to a moderate and pragmatic leader. While the symbolic alliance with Hollande is a step in that direction – and it is more than welcome – the fact of the matter is that Tsipras needs to show his accession to pragmatism, and therefore make a clear shift to political responsibility and accountability, not just with symbolic gestures, but with actions.

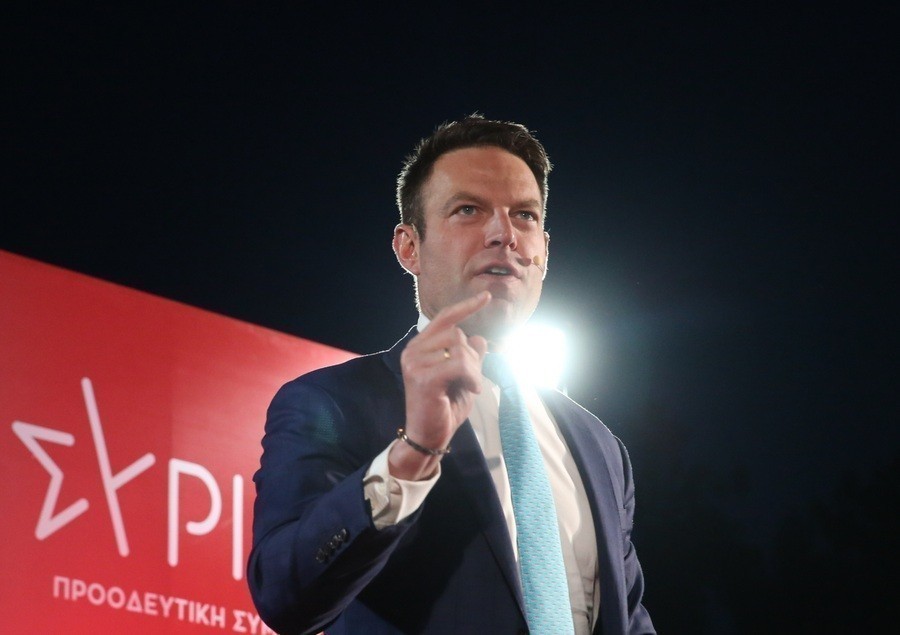

Tsipras was elected as Greece’s prime minister in January 2015, when the Coalition of the Radical Left known as Syriza won a resounding electoral victory and formed a coalition government with the small, far-right, Independent Greeks. Tsipras was able to become Greece’s youngest prime minister in 150 years by transforming Syriza from a small far-left fringe party to an electoral powerhouse, by capitalizing on Greek voters’ disenchantment and by imitating the socialist party’s (Pasok) radical style: a mix of populist language and grand promises of change through the expansion of the public sector, which many voters associate with better times, since Pasok towered over Greece since 1981. Tsipras and Syriza staked a tie-less election campaign repudiating the steep budget cuts Greece agreed to, thereby aiming to end the vicious circle (favlos kyklos) of austerity, as well as the unprecedented misery and anger caused by it.

Syriza was the first party to be explicitly elected on the promise of challenging the austerity policies that have prevailed in the EU since 2010. Correspondingly, the government’s campaign promises spurred mixed feelings and reactions across the continent. Subsequently, what followed was an intensive, complex and largely opaque five-month ‘negotiation’ which led to a cliff-hanger, bringing the country on the verge of bankruptcy, and thereby making a “Grexit” seem more possible than ever. Eventually, in July, Tsipras pulled a U-turn (what Greeks call kolotoumba) and accepted a new bailout deal, extending the fiscal adjustment and structural reforms prescribed in the previous agreements by Greece’s creditors. Thus, Tsipras’s confrontation with Greece’s creditors triggered bank runs, thereby leaving the economy in shambles and impairing a recovery from the country’s never-ending slump.

The 180-degree turn by the Greek premier, and his choice to embrace the same economic reforms he once condemned, prompted a rebellion by various leftist hardliners, thereby triggering another general election (the fifth one in six years). Evidently, Tsipras was successful in his calculations: the pain of the “negotiation”, together with the imposition of capital controls didn’t prevent him from securing another resounding electoral victory. By neutralizing his opponents both within his party and the entire domestic political system, Tsipras undoubtedly emerged as the absolute master of the Greek political scene. Consequently, the country’s future greatly depends on the direction Tsipras orients his party and the country, as well as the determination and efficiency he illustrates in implementing the agreement he signed.

Overall, the result of the most recent elections, which took place on September 20th, presented an unprecedented opportunity for the country. In this context, as many observed, Tsipras can now make-up for the mistakes and the damage done by his first administration, both on the domestic and the foreign front. While Tsipras’s choice to form another coalition with the far-right and populist Independent Greeks, instead of a government of national unity/purpose with the center-left and pro-EU parties, such as Pasok and The River, together with the government’s general composition – which barely differs from its predecessor – is rightfully perceived as a missed opportunity, it is essential to look at the broader picture.

All in all, Tsipras’s new administration will enjoy greater political stability than any of the previous crisis governments. Ironically, in spite of the fact that the new bailout plan is expected to be more painful than its predecessors, at the same time, it also gained unprecedented support in the Greek Parliament (approved by an overwhelming majority of 222 out of 300 votes). Thus, the vital point is this: Tsipras’s electoral victory in September marked the first victory of a party on the premise of pledging to implement, rather than tear apart (or re-negotiate) the country’s bailout program. Clearly, now that Tsipras has gotten rid of the hard left platform – the rebels – of his party, he can make the ever-needed shift towards a more moderate and realist approach of leadership.

Accordingly, Tsipras needs to implement the milestones and the necessary reforms quickly, in order to secure a successful first review – a sine qua non for the disbursement of funds by the country’s creditors (with the most recent addition of the European Stability Mechanism, the so-called “troika,” was re-named into the “quartet of institutions”). Next, he can secure access to lower-cost liquidity and include Greece in the ECB’s quantitative easing program and thereby prevent a bail-in of un-insured deposits, as well as a phase-out of the stringent capital controls. Most importantly, by implementing the milestones and reforms quickly, Tsipras will be able to begin the fundamental part of the discussion: debt relief.

Overall, the Greek people need to be offered incentives to embrace change. In this notion, the crisis-ridden public rightfully deserves to see that there is light at the end of the tunnel. Therefore, Greece’s creditors need to meet Tsipras half-way and make a clear trade-off with structural reforms. Correspondingly, the more Athens does to fix its chronic pathologies such as clientelism, cronyism and rent-seeking, the less obstinate the creditors should be about short term fiscal targets and primary surpluses. Last but not least, as it has become clear from a series of publications and statements both by the IMF and, most recently, by the president of the ECB: one way or another, Greece needs a sizeable write-down of its mountainous and unsustainable debt, which is projected to reach 198 percent of GDP in 2016. Due to the inherent hurdles and the lack of political will in selling this to voters, extending the grace period on debt repayments, reducing interest rates, and tying service payments to Greece’s growth rate are ways of providing debt relief without writing it down, per se.

Most importantly, the process of reforming Greek institutions and markets cannot just be something imposed by external forces. While it is indisputable that Greece needs to implement radical reform, remove bottlenecks, and cut the extremely high administrative burdens that make the country’s business environment hostile, it is imperative that the country takes ownership of the reforms, in order to become a modern, functioning democracy. As Hélène Rey perfectly put it in an article for the Financial Times, “Institution building, not [Grexit], is what [will] put the Greek economy on a sustainable path for growth.”

Both Hollande’s visit to Athens and Tsipras’s most recent trip to the United States demonstrate that the world is ready to reward the prime minister for his shift to pragmatism. By learning from his mistakes, committing himself to the implementation of the much-needed reforms, and thereby transforming himself into the “Lula of the Mediterranean,” Tsipras will be able to generate waves of positive expectations, thereby encouraging and stimulating investment, employment, and growth. More importantly, by saving the Greek economy from its never-ending tailspin and therefore reversing the trend from austerity to growth, Europe will be able to make it clear to the world that it can once again be a promising place of sustainable and inclusive growth, as well as a path-breaking economic and political peace project.

Posted by The SAIS Observer Staff on November 10, 2015